Ready, steady...go!

The Play Observatory survey is now live! Cath Bannister discusses what we mean by ‘play’ and what we are collecting.

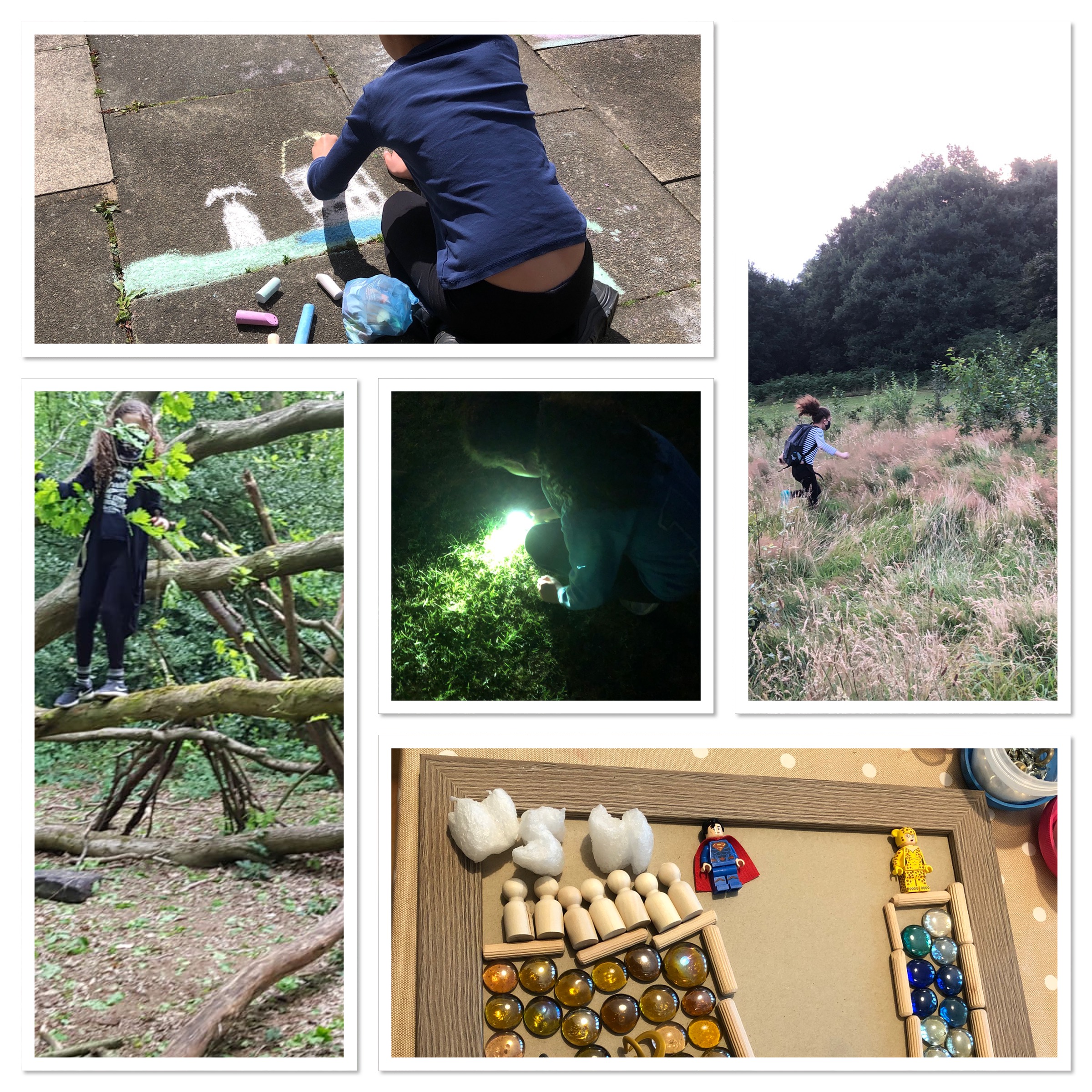

It’s an exciting time at the Play Observatory with the launch this week of our survey into children and young people’s play during the COVID-19 pandemic. We’re inviting children to share their play experiences with us through written accounts, audio and video recordings, photos and images. And their family members, and adults including teachers and youth group leaders, are also encouraged to contribute. The examples shared with us will give us valuable insights into how play has been affected by the pandemic, as well as its impact on children’s wellbeing.

But what do we mean by ‘play’? It seems intuitive to consider play as something children do; something that involves a lot of physical movement, dressing up and toys, and an active imagination. However, apparently common-sense definitions can be restrictive. For example, is video-gaming ‘play’, or watching YouTube clips or using apps like TikTok? What about activities that involve grown-ups too, like family pizza and movie night, structured games or craft sessions in a youth group setting, or board games and quizzes played together by all generations?

How about telling jokes, singing and rapping, doing impressions, writing a poem, taking part in hobbies or street sports? Then there’s the customary and faith-based events which structure our year. When the Tooth Fairy or Father Christmas pays a visit, or when we spin the dreidel at Hanukkah, is that play too?

The play theorist Brian Sutton-Smith recognised what he called the ‘ambiguity’ of play, suggesting that how we understand what play is, is culturally informed, with some types of play privileged over others. In societies with a westernised outlook, for example, play has become seen as the preserve of children and can be used as a shorthand for childhood or even childishness (in contrast to the serious business of being a grown-up) as well as being associated with development. Sutton-Smith pointed out that almost anything can include aspects of playfulness, that play is diverse, and unrestricted by age. His seven ‘rhetorics’ identifying dominant interpretations of play - progress, fate, power, identity, imaginary, the self, and frivolous - consider how learning, games of chance, sports tournaments, community festivals, creativity, solitary pastimes, and playful jokes and pranks can all be considered play.

We can’t wait to hear about your play about and during the pandemic, in whatever form it takes. You can share your games - and any adaptations you’ve made to them - and also your favourite jokes and songs, memes or clips, online play, and what you’ve done at special times of the year.

Please join in and play your part!