Everyday play in the archives - documenting how children’s play changes but also stays the same

Yinka Olusoga explains some of the history of researching children’s own ideas about their everyday play.

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed how we currently live but the ‘everydayness’ of our lives continues, and for children (and adults) play is part of this. Everyday play can be an escape from the pandemic. It can also be a medium for making sense of it and the shifting circumstances it imposes, as seen, for example, in the Coronavirus hospitals that some children have constructed in Minecraft (like the one pictured). Maintaining social distance, and spending much more time in our homes, has made us develop new habits and skills for play and for entertaining ourselves, and sometimes prompted us to relearn old ones. Children and adults have played online, but they’ve also rediscovered boardgames and used chalk in the street to play games or leave messages.

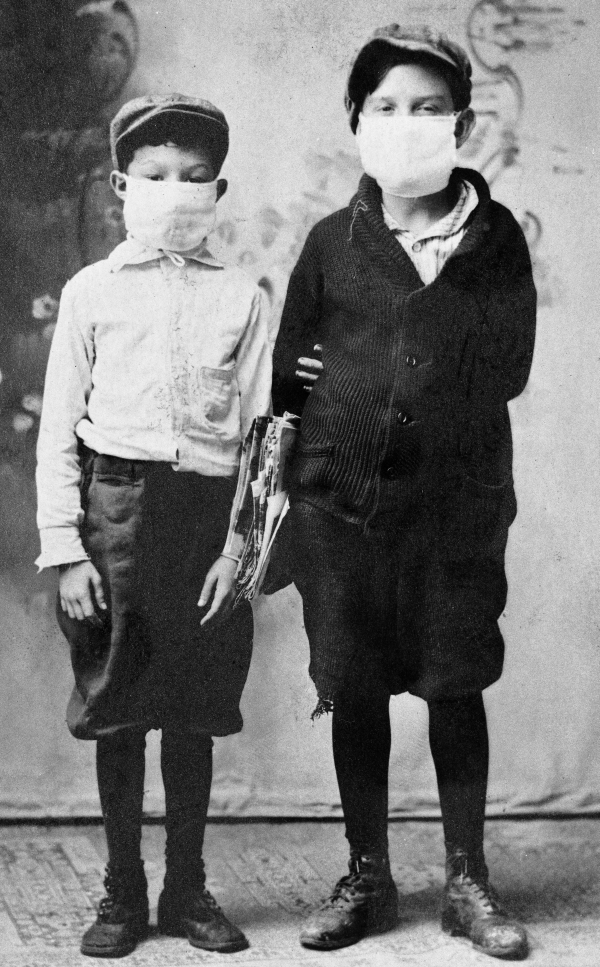

As an historian, it is interesting to experience a big historical event. How we experience time, location, travel and social interaction is currently different. Plus, although we know roughly when the pandemic started, we do not yet know when it might end. A recurring theme in the history of pandemics is how quickly societies forget about them when they end. We forget about the words and practices that became the ‘new normal’ for a while and how it felt to live through it. This forgetting happens even when, as in the case of the 1918 flu pandemic, photographs, newspaper reports and materials from them can be found in the archives.

And when we do keep records of everyday life, in ordinary or extraordinary times, it tends to be adult life that is most consistently captured. But what about children’s lives, and their play in particular?

In the 1950s, shortly after the end of the Second World War, Peter and Iona Opie began to collect information from children on their play, language and folklore. The Opies were interested in the play between siblings and with classmates, play between best friends and play in groups, wherever it happened. They collected everyday play, recording its persistence, and tracing how elements of it are transmitted, evolve and sometimes die out. Thanks to the support of teachers, they learned about play directly from children, collecting their testimony in their own words. This work established a foundation for a great deal of other research into children’s culture.

Inspired by the Opies, the Play Observatory asks the question ‘What is children and young people’s everyday play like now, when life is not ordinary thanks to COVID-19?’ We want to capture and preserve a record of children’s play in 2020 and 2021, in all of its forms and locations, across the various stages of the pandemic. With the support of their adults, we want children to be able to tell us about their play, what it meant to them, how it made them feel and what talking about it helps them to remember and share.

Can you help us? Play your part in the Play Observatory by responding to our online survey.

Follow us on Twitter @PlayObservatory to be the first to hear updates.